The “Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition” (1914-1917)

In 1913, Sir Ernest Shackleton placed an advert in The Times in search of suitable men for the crew of his expedition to cross the Antarctic:

‘Men wanted for perilous voyage. Low pay, bitter cold, long months in complete darkness, constant danger, return uncertain. Honour and recognition if successful.’

Despite this honest and unembellished description, the number of applicants (5,000) greatly exceeded the number of crew members needed (56 on two ships).

However, the expedition failed even before it really began: Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, was trapped in the ice and sank, but the ‘Boss’, as his men respectfully called him, ensured that all of them returned alive in one of the most incredible rescue operations in polar history.

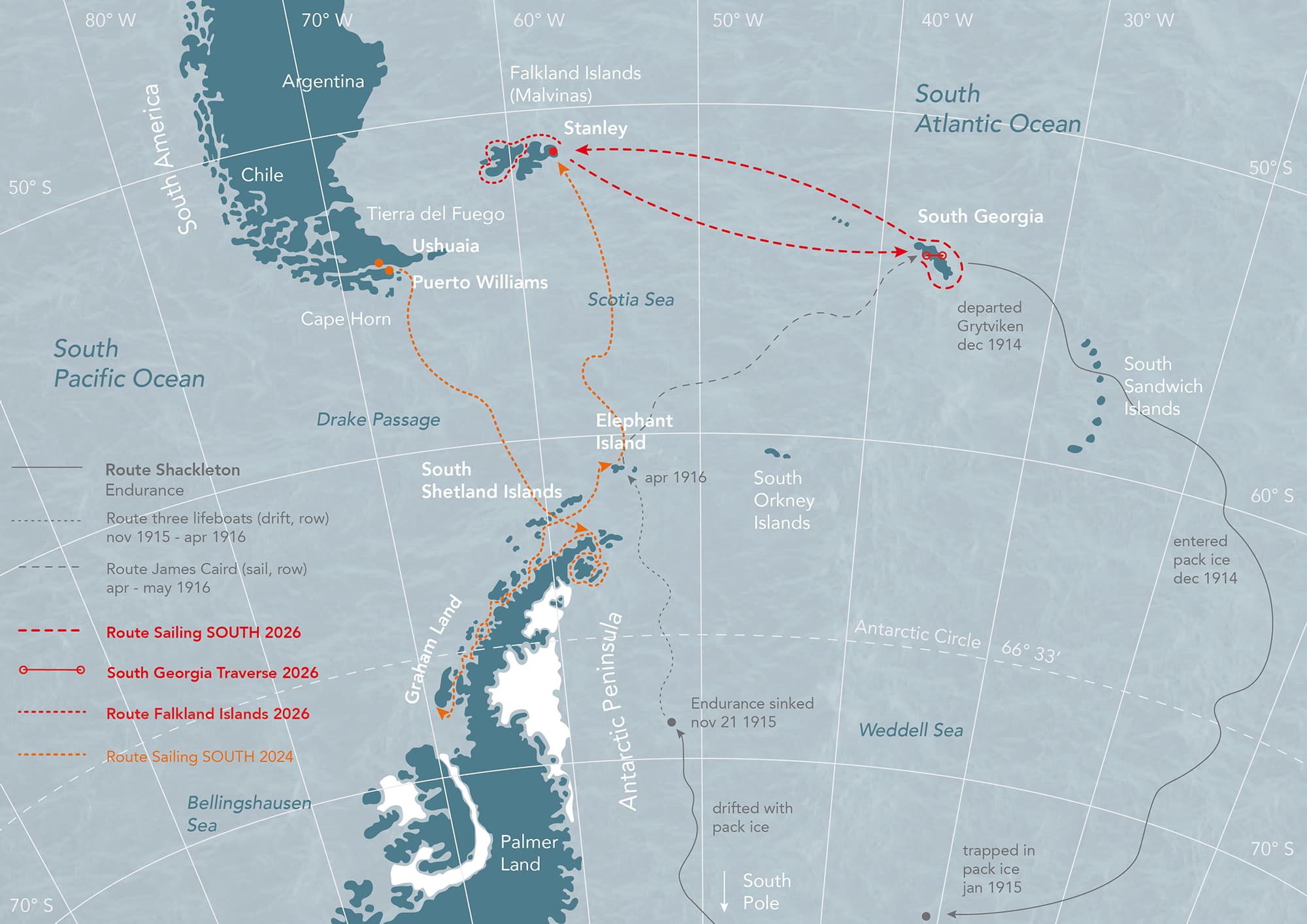

The ‘Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition’, which had no less a goal than to cross the Antarctic continent, was doomed shortly after its start in South Georgia in December 1914. Early on, drifting ice in the Weddell Sea hindered the onward journey south. By January 1915, the ship, the Endurance, was completely trapped by the ice. She drifted for several months, trapped in the ice through the polar winter, but could not withstand the pressure of the ice masses breaking up and drifting in the spring. The Endurance was abandoned in October 1915 and finally sank, crushed by the ice, on 21 November 1915, watched by Shackleton and his men.

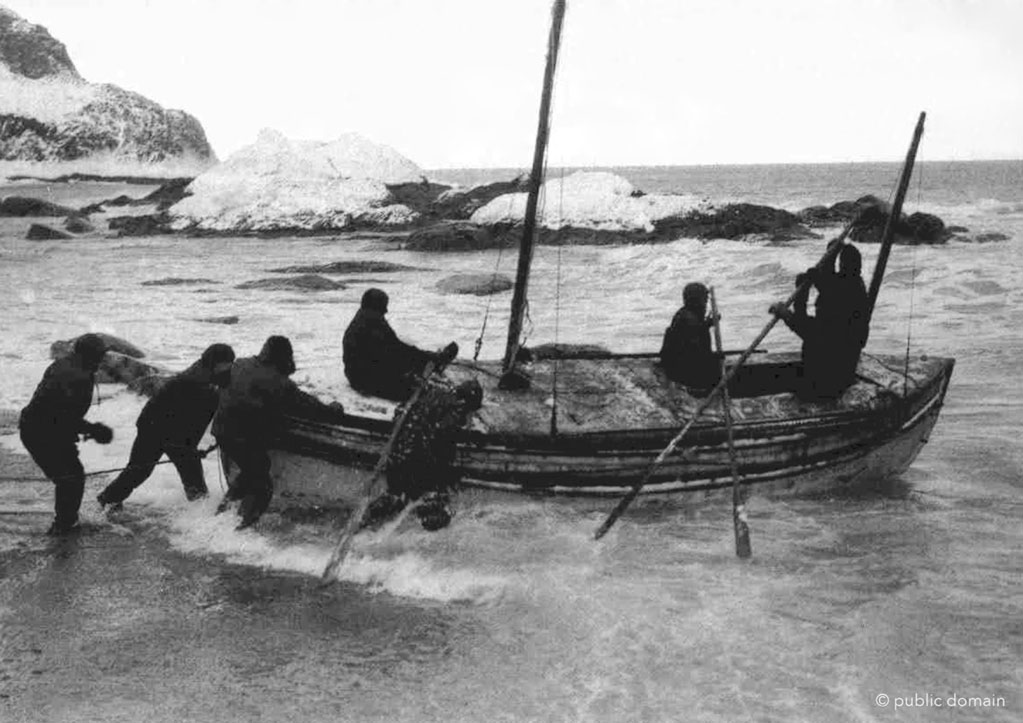

After months in a camp on the cracked, drifting and melting ice, it finally broke completely beneath their feet at the end of summer in April 1916. Shackleton decided to head for the nearest land over open water with the three lifeboats that had been carried up to that point.

After five days of rowing through the stormy, icy Weddell Sea, the exhausted 28 men reached Elephant Island and, after 497 days at sea and on sea ice, had solid ground under their feet again for the first time.

Elephant Island, that tiny island – today as then located far from any known shipping routes in the Antarctic Ocean – barren, rough, almost completely glaciated except for a narrow strip of rock on the beach, and mercilessly exposed to wind and weather, offered the Endurance crew no protection and no prospect of rescue from outside.

And so Shackleton decided to set out again to get help. With five other men, including Frank Worsley as navigator, he wanted to try to reach the occupied whaling stations on South Georgia, which were over 800 nautical miles away, in one of the open lifeboats.

At the end of April 1916, the six of them set sail in the James Caird, which had been reinforced and converted by the ship’s carpenter for this daring crossing. The remaining 22 men stayed behind on Elephant Island under the care of Frank Wild, where they had to wait another four months for their rescue, which they could hardly hope for at the time.

It took Shackleton and his crew 15 days to make the dangerous and rough passage through the storm-lashed South Atlantic before they actually reached the coast of South Georgia, thanks to the navigational skills of Frank Worsley. However, they landed on the ‘wrong’ side of the island, the uninhabited south side, and in a boat that was no longer seaworthy. The exhausted men went ashore at King Haakon Bay.

After a few days of rest, they had no choice but to attempt to cross the island, which consists mainly of glaciated mountains up to 3,000 metres high, in completely unmapped terrain, on a route never before taken, and without adequate equipment, if they did not want to give up on saving themselves and their comrades. The risky and daring undertaking was a success, and as if by a miracle, after 36 hours of uninterrupted marching, they reached the whaling station at Stromness with their last ounce of strength on 20 May 1916.

From there, after three unsuccessful attempts, Shackleton finally managed to rescue all the remaining members of the expedition from Elephant Island at the end of August 1916 and take them safely on board the Yelcho, a Chilean Navy guard boat.

‘South’ is the title of the book Shackleton wrote about the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

This can also be found in the name of our first expedition “Sailing SOUTH 2024”. 110 years after the Endurance, for the 150th birthday of the “Boss”, we set off in February 2024 and followed some of his tracks in the Southern Ocean to Elephant Island.

With ‘Sailing SOUTH 2026’ we want to set sail again, continue the journey and set course for South Georgia, to cross the island on skis and sleds in the footsteps of Shackleton and discover this storm-lashed Antarctic oasis, 110 years after the ‘Boss’ and his men.